What Are Chinese Martial Arts?

Martial arts.

Two words which evoke a wide range of ideas and conceptions, both from experience and fantasy.

For many who grew up in the West, “martial arts” conjures up mental images of red neon signs promoting local Karate, Taekwondo, or Brazilian Jui-Jitsu schools.

Those words remind others of mass-commercialized combat sport spectacles such as Boxing, Wrestling, and MMA.

And for most, memories of watching iconic Bruce Lee films.

However, little is known in the West of the ancient and rich traditions of Chinese martial arts.

Names like Guan Yu, Wang Lang, Dong Haichuan, Wong Fei Hung, or Gu Ruzhang hold little-to-no significance in the western consciousness, but are infamous figures in many Chinese martial arts traditions.

The words “martial arts” have also come to take on a synonymous connotation with “self-defense”, with classes and seminars offered in virtually every city and town geared towards those wanting to learn techniques for countering an assailant.

Yet, how many of these “martial arts” classes stress daily meditation and stretching practice?

How much emphasis do these classes place on stance and weapons training?

The history and development of Chinese martial arts systems have nearly always extended beyond mere “self-defense” in the individual “what to do in the event of an attacker” sense, but rather developed as communal practices for common defense.

Rural villages, spiritual temples, and even large-scale regions would rely on their martial combat skills to defend against raiders, protect traders from marauders, and even to repel invading armies.

Chinese martial arts, since their inception, have aimed to cultivate the preservation of life - to preserve one’s self against an attacker, to preserve one’s body against decay, and to preserve one’s community against incursion

The Legend of the Yellow Emperor

Considered the mythical founder of Ancient China, living at the turn of the 3rd Millennium BCE, the Yellow Emperor is revered as a semi-mythical, semi-historical figure responsible for bringing civilization to ancient China.

The earliest documented mention of the Yellow Emperor can be traced to the 1st Century BCE document Records of the Grand Historian (太史公書 - Tài Shǐ Gōng Shū, or 史記 - Shǐjì, for short).

Recalled as a legendary military leader, the Yellow Emperor is considered one of the earliest founders of Chinese martial arts. The Shǐjì credits the Yellow Emperor with inventing “horn-butting”, a precursor to Chinese wrestling, as well as being a master military strategist and fighter.

In the centuries and millennia since his supposed lifetime, Chinese martial arts evolved into a plethora of countless systems and lineages, many lost to history due to the lack of written records.

But nearly every Chinese martial arts tradition traces its origins back to the Yellow Emperor.

Metaphysics, Ethics, and Vitality

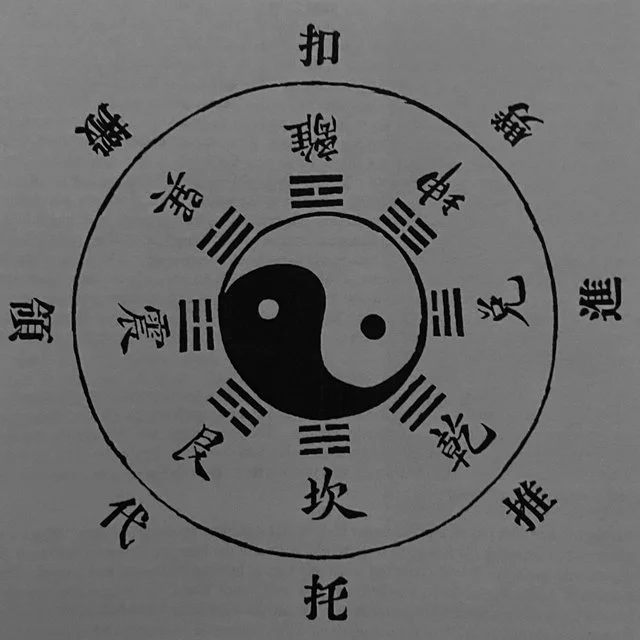

Dating back to around the 10th century BCE, the pre-Taoist divination bone carvings are thought to have emerged, containing the earliest precursor to hexagram notation, which would become the basis of the infamous I Ching divination text.

Hexagram theory and Taoist practice would come to heavily influence the development of internal kung fu styles such as Taijiquan and Baguazhang. Metaphysical considerations sought to express cosmic creation concepts through martial systems, such as the transition from Wuji (無極) to Taiji (太極) to Liang Yi (兩儀).

Over the course of the proceeding centuries, the emergence of ancient Chinese philosophical systems-Taoism, Confucianism, and later Buddhism-would seamlessly infuse into the burgeoning boxing and wrestling combat systems.

The inclusion of ethics and metaphysics into martial training stressed the critical importance of living a moral life and harboring a deep reverence for living beings.

The aim of a martial arts practitioner was to cultivate an inner harmony while still developing outer martial strength.

As ancient Chinese understanding of the human body developed, the concept of Qi (氣)-“vital energy” or “breath”-was developed and with it the earliest breathing meditations, or Qigong (氣功) - “breath work”.

Through the modern day, Qigong has been a fundamental practice in most, if not all, Chinese martial art systems, as a means for improving health and prolonging one’s life.

And thus with the incorporation of metaphysics, ethics, and vitality at the core of martial arts training, the aim of the practitioner has been far beyond mere “self-defense”, but rather as a practice of preserving and prolonging one’s life.

The Shaolin Legend

As the centuries went on, martial combat and philosophical systems continued to coalesce into more and more diverse styles and lineages.

Traditions attest the development of systematized martial arts at the legendary Shaolin Temple.

An inscription dating from the 8th-century CE found at the Shaolin Temple depicts Shaolin monks engaging in combat: one instance of the monks defending the temple against bandits, the other of Shaolin monks aiding the Tang Dynasty emperor Li Shimin (李世民) against a warlord.

Surviving texts from that same time period which mention Shaolin monks being skilled at staff combat, while texts from the 14th-century affirm that martial arts originated at Shaolin.

While there are plenty of oral traditions and credible evidence that support the existence of combat systems dating far back into antiquity, it was during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) that martial arts systems began to formalize into traditions that would influence the styles we know of today.

Many modern traditions claim ancestral influences back to the Ming Dynasty (and some even far earlier), such as Chen-style Taijiquan, Xingyiquan, Bajiquan, Tanglangquan (Praying Mantis), Wuxingquan (Five Animals), and many more.

Defense of the Nation

The birth of modern Chinese martial arts can be traced to the Manchu invasion of China, overthrow of the Ming, and establishing of the Qing Dynasty, which would rule China until the 20th-century.

During this turbulent time, Chinese martial arts became an icon for national defense.

Many later stories, poems, songs, and films recount the bravery Chinese martial artist had in defending China against the Manchu invasion, and the multiple subsequent uprisings and rebellions.

As a result, legends attest that many anti-Qing Shaolin monks fled south to avoid persecution, later mythologized as “The Five Ancestors” leading to the development of Southern Chinese martial arts, such as Wing Chun.

Chinese Martial Arts in the Modern Era

After the fall of the Qing Dynasty and the establishment of the Republic of China in 1912, Chinese martial arts underwent drastic codification and nationalization, resulting in the Guoshu (國術) era, or “national sport”. Guoshu sought to unify the various Chinese martial arts traditions and lineages, establishing centers in major cities across China in an effort to preserve the traditional combat arts, with the Central Guoshu Institute (中央國術館) being founded in 1927.

This process continued until the Japanese invasion and outbreak of the Chinese Civil War in the late 1930s.

Following the decade of warfare that scarred China, the People’s Republic of China was established, and with it, Wushu (武術) (“martial arts”) emerged as the new national sport, emphasizing acrobatics, health, and competitiveness in Chinese martial arts.

After the diplomatic opening up of China in the 1970s, and the decades that followed, Chinese martial arts rapidly spread all across the globe, with its influence extending to Hollywood with the rise of popular martial arts films with stars such as Bruce Lee, Jackie Chan, Jet Li, and Donnie Yen.

Today, Chinese martial arts communities can be found in nearly every corner of the globe, promoting and preserving the lineages and traditions that stretch back into the furthest recesses of legend, myth, and imagination.